Health lost its primacy in the way we plan our urban spaces. After flood, pandemic and fire, it’s more urgent than ever to recognise its importance.

People are left picking up the pieces after floods ripped through the east coast of Australia, and questions are being asked about whether devastated cities like Lismore can or should be rebuilt.

As wild weather and extreme temperatures become more frequent, Australians must decide how to rebuild, and where it’s safe to do so. But while doctors are increasingly dealing with the effects their patients’ living environment has on their health, town planning across the nation all but ignores health and health professionals.

Western Sydney GP Dr Kim Loo has long been driven to ensure doctors get a say in urban planning. It’s clear to her, that social, geographic and infrastructure factors play a role in her patients’ wellbeing, an insight she attributes to having a mum who was a social worker.

“When I take a medical history, I say ‘Where are you living? Do you feel safe in your home? Is it hard to heat and cool your home?’”

The health of Dr Loo’s patients is already affected by climate change.

Rising temperatures have hit Western Sydney particularly hard, with the mercury almost topping 50 degrees in Penrith suburbs in early 2020, making it the hottest place on earth that day.

She points to the harm that excessive heat has on pregnant women.

“Prolonged exposure to heat impacts growth and increases the risk of premature labour,” says Dr Loo. “In schools, we know that children learn optimally at a temperature between 22 and 24 degrees. [In some of these schools] they don’t even have air conditioning.”

That kind of heat also ramps up cardiovascular stress, asthma, mental illness, renal disease and even death.

Western Sydney is also home to many people on low incomes.

“Once you pay the rent there’s not much left for food and medications, and everything else (like cooling and heating) is expensive,” Dr Loo points out.

“We’ve got pamphlets for patients now on ways of cooling their home, how to keep hydrated and be safe in the heat,” she says.

But part of the problem is the way housing is designed.

It’s not fit to cope with more extreme temperatures and weather events.

‘We’re building ovens’

In NSW, the state’s environmental planning policies are being reviewed for ways to improve the quality of new builds.

“The building industry has been self-governed, and there’s the problem,” says Dr Loo. “The idea of the [policies] are to improve the basic standard, which has been very poor.

“Western Sydney is just building ovens,” she gives an exasperated half-laugh, “and it’s the health sector that’s going to bear the consequences of that.”

Dr Loo is one of a long line of health professionals who have fought to make health a priority in urban planning.

In 1856, decision makers in Sydney were faced with a higher child mortality rate than London during its infamous 1845 cholera outbreak.

They knew the “large surplus mortality” arose from causes that could “be made to disappear”. Namely, managing the city’s sewage and ensuring citizens had access to clean water.

Dr William Bland, an elected Member for Sydney in the newly formed Legislative Council of NSW, campaigned hard for health to be made a central consideration in the planning of new suburbs, towns and infrastructure.

“There is no price … too high, in order to secure to the inhabitants of our towns and cities, the greatest attainable amount of health and longevity, as well as protection from actual disease,” he said.

He was optimistic about the role this initiative would play in the health of communities into the future.

“The day cannot be far distant, we would … hope, when the first consideration in the selection of the site of any future town or city will be its probable ‘healthiness’ or ‘unhealthiness’,” he mused.

He may as well have waited for Godot.

Planning has since become very complex in Australia with thousands of regulations and decision-making processes, different in each jurisdiction.

Yet over a century and a half later, Dr BastianSeidel, another doctor elected to a state parliament, says health is still not a compulsory part of the decision-making process.

Dr Seidel represented the rural electorate of Huon, where he is a practising GP, in the Tasmanian Parliament. He was also the shadow minister for health and a former president of the RACGP. He has a uniquely informed perspective on how government, planning and health intersect.

“None of the planning schemes … consider developments and the impact on health services at all,” he tells me.

An example is the Huntingfield subdivision in the Kingborough local government area.

“This is the largest land release ever in Tasmania,” he emphasises. “But there was no planning with regards to implications on ambulance services, medical services. It just didn’t exist.”

The development includes a proposed 470 lots for townhouses, units and larger homes, and includes affordable and some social housing.

Communities Tasmania, the government department that oversees social and affordable housing, boasts on its website that half the development site will be set aside for green space and recreational use. The project will have commercial areas, and aim to include businesses such as cafes, hair salons or convenience stories.

It does not, however, outline specific plans for any medical or health services.

A spokesperson from Communities Tasmania says their master plan “allows for commercial sites where private medical facilities can be considered”.

Although the provision of services “must be demand driven”, according to the development’s consultation report, which suggests “health and community services will expand to meet growing need”.

Dr Seidel asked Communities Tasmania about this at the consultation session in September 2020.

“You’re putting 400 new houses in there, so you have 1000 new people in there,” he recalls saying. “Where are they going for medical care?”

He says the response was an offer to add a building that could serve as a medical practice.

But people moving into the subdivision would have a reasonable expectation of access to medical services, and an empty medical practice would do nothing to help them.

“Do we pluck those doctors and nurses out of thin air? Are we recruiting them actively? And if you can’t attract them? Have you actually asked around in other facilities where they can actually meet the demand?” he pressed on.

“There was no answer. There was no planning for that whatsoever.”

Something chronic

While urban planning has its roots in tackling acute health issues, there’s growing realisation that it will also be vital in combatting growing rates of chronic disease.

“A person’s health is as much shaped by contextual factors as it is dependent upon individual and behavioural factors,” writes urbanism expert Dr Jennifer Kent in her book Planning Australia’s Healthy Built Environments

“But we forgot about the link between urban planning and health until more recently, when we’ve now seen a shift away from acute illnesses to more chronic, non-communicable lifestyle-related diseases like heart disease and diabetes,” the University of Sydney researcher says.

Dr Kent is part of a growing cohort of urban planners with an expertise in health. She says healthy cities have a structural foundation. Things like transport, density, distances to facilities and open space directly affect risk factors implicated in a lot of human disease – inactivity, isolation and food.

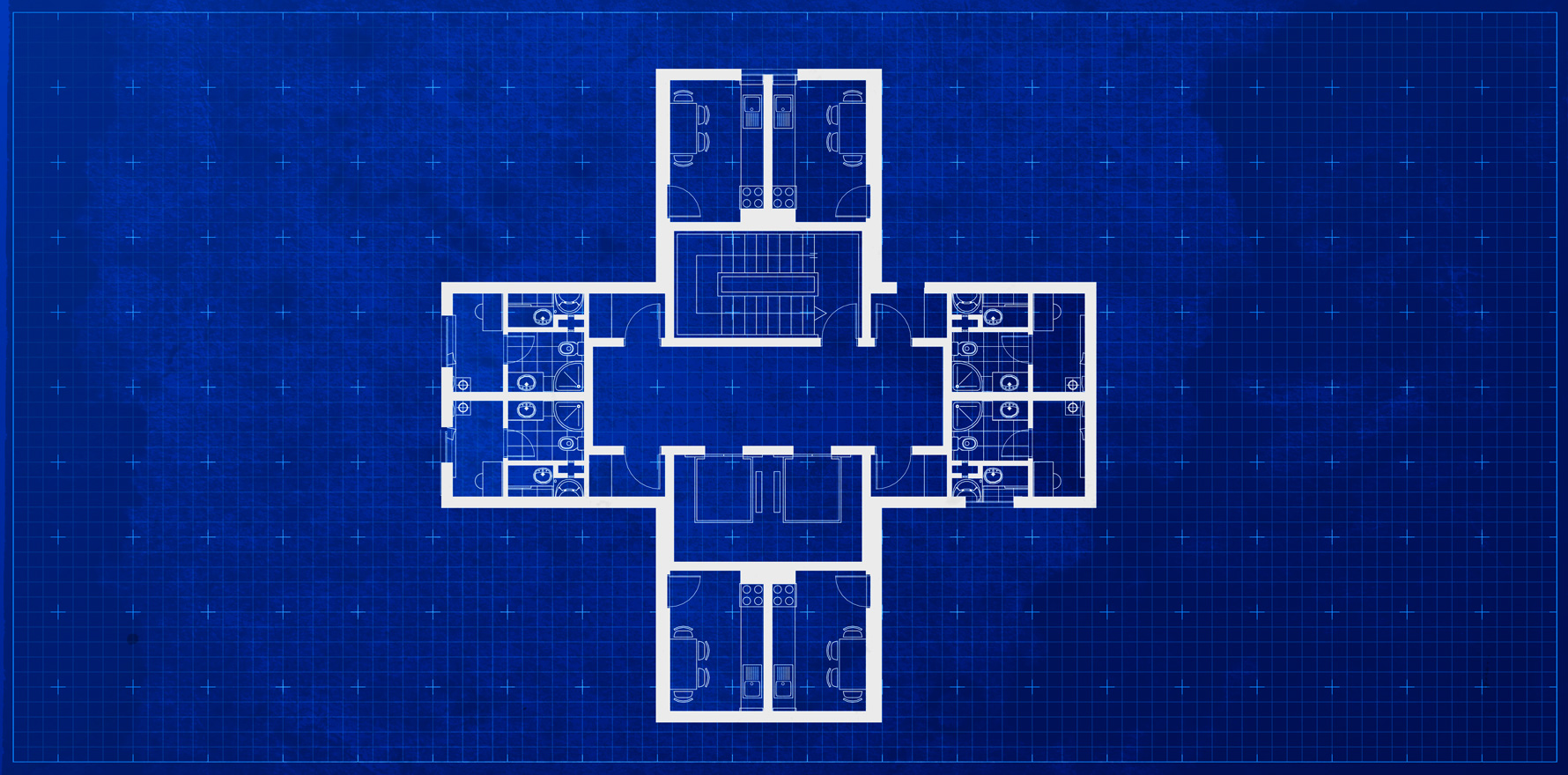

A very wide range of decisions come under the purview of planning – everything from pet regulations to making sure newly built homes have practical kitchens with enough room to swing a (hypothetical) cat in. They decide if your open space is a green park or a car park; how far the shops or the local pool are, and whether your walkable food source is a supermarket or a greasy takeaway.

Density is a controversial topic in urban planning, but Dr Kent points to some benefits of building up, rather than embracing suburban creep.

“We can provide opportunities for incidental and recreational physical activity, but we can also structure our cities in a way that ensures that people have time for those kinds of things,” she says.

In low density cities, people spend hours travelling because everything is farther apart. That means less time to exercise, buy fresh food, and cook healthy meals. Housing also swallows up valuable farmland on the outskirts of urban centres.

“The Sydney Basin is very arable land, but with greenfield development, those sites will never be used for growing fresh food ever again,” Dr Kent explains.

Professor Billie Giles-Corti, director of the Healthy Liveable Cities Lab at RMIT, warns that what leads to better health outcomes can be counterintuitive.

For instance, when higher density is proposed in an area, community groups will often oppose it.

“Now, from my point of view, as a person who’s an expert in this area, that’s disastrous, because we do need to have more people live in established areas where there’s amenity, from an equity point of view,” she says.

“We have to change the way we build our cities,” she continues. “We need transformation.”

Dense, but disconnected

Professor Giles-Corti is adamant that decisions about densification must be driven by evidence in order to achieve better outcomes for the community and ensure more people have access to high quality amenities.

Unfortunately, Brisbane politician Jonathan Sri says, the kind of higher density actually delivered in Australian cities is nothing like older apartment neighbourhoods in European cities where people chat on footpaths or from balconies and there’s both a physical and emotional connection to the streetscape.

Instead, it’s more along the lines of an urban compression model, where residents still drive their cars, park in the basement and catch a lift up 20 floors to a small flat with no connection to the street, neighbours or the community.

Well-designed buildings are not in the affordable range, he says. The rest are often cramped, low-quality flats, without much light or airflow, that are energy intensive to run and maintain.

Councillor Sri represents The Gabba, an inner southern Brisbane region experiencing rapid growth in population and apartment block developments.

“Health frameworks don’t really play a strong role in urban planning in Brisbane,” Councillor Sri says.

“There aren’t health practitioners or health experts at the table when these planning decisions are made, which is wild.”

COUNCILLOR JONATHAN SRI

“That’s definitely not how it should be.”

“We’re making two big mistakes in Australian cities,” he says.

“We’re still continuing to sprawl further out, and we’re cramming more density into neighbourhoods that are already dense enough. Meanwhile, the greater proportion of existing suburban neighbourhoods aren’t densifying.”

Inner-city suburbs were always designed to be walkable because they pre-dated the car, says Councillor Sri,. And they already have the critical mass of people to sustain public transport and other infrastructure.

But it’s politically difficult to overcome resistanceto density in the suburbs, and cheaper and easier to develop inner city warehouses or existing small blocks than to buy up several privately owned blocks further out, he says.

“At a political level, planners and politicians have said, ‘Okay, we’re going to keep densifying the very innermost parts of the city. And we’re going to keep sprawling outwards. But we’re not going to engage in the more politically contentious conversation about densifying car-centric suburban neighbourhoods’.”

Councillor Sri says speculative property investment is part of the problem in the area he represents.

“We’re seeing a lot of new development, often designed to maximise the profit that can be extracted from the site. That means developers cramming as many apartments onto a block as they can get away with. And in many cases, that’s leading to suboptimal design outcomes that aren’t seriously considering the long-term interests of the residents who end up living there.

“Alongside that we’re still seeing both building and transport design that prioritises private motors vehicles. Even though the neighbourhood is getting denser, which theoretically supports more public transport, the council and the state government are still mostly investing in road projects that encourage more people to drive.”

One of the biggest infrastructure gaps is in public green space, he says, with higher pressure on existing parks as more people move into the area. There’s a lot of competition for the little there is, whether it’s dog walkers, people exercising, kids playing or older people walking.

“The majority of inner-city residents are renters. Property developers are designing for investors who won’t actually live in these neighbourhoods. So there’s often a very big disconnect there between what the developers are delivering and what actually meets people’s long-term needs.”

It won’t matter to developers if air-conditioning units are hard to clean and don’t provide good quality air in 10 years’ time, says Councillor Sri, because they’re not in it for the long haul.

“And the standards and regulations are pretty loose. So no one’s really thinking about the long term health of residents.”

“While health and environment intersect, health goals should have their own specific protections.”

COUNCILLOR JONATHAN SRI

Dr Seidel echoes this sentiment.

“I believe there should be a framework – a health service impact assessment – also in place. And developers, councils or state governments need to understand and demonstrate how they meet the health service impacts in new developments.”

But he warns against tokenism. A park on a plan is just one piece of the puzzle and won’t replace health services, doctors, community nursing staff or ambulances.

“To be able to live life to the fullest and in a meaningful way, it takes more than just allocated green areas.”

Ask your doctor

The key is for doctors to have a voice in planning, Councillor Sri says.

“It is really important, because how our neighbourhoods are designed fundamentally shapes how we live, and our health, as individuals.”

But he believes planning decisions are increasingly inaccessible to anyone outside of politics and the property industry.

For Dr Loo, the best way for doctors and other health experts to get involved is through joining networks, creating awareness and, in doing so, increasing the chances that those educated voices get a seat at the table.

She is currently NSW Chair of Doctors for the Environment Australia, on the Council of the AMA (NSW), co-chair of the Hills Doctors Association, and a member of Hills4ClimateAction and AustralianParents4ClimateAction, among other community groups.

“We are working as hard as we can to have a better built environment for the climate impacts that are already baked into the system, educating people and talking with politicians for the past six years,” she says.

While they’ve had some successes, she says “it’s all piecemeal”.

“Councils are a really important place to start, even though the state can overrule anything the council does. And you need a good planning minister. It really requires advocacy from all areas.”

Penrith Council is now proposing to ban dark roofs on new houses in the LGA and mandate a cool refuge: a room that will remain below 28°C “provide temperatures of no more than 27°C on extreme heat days and should also aim to achieve between with 40% to 60% relative humidity.

Dr Loo’s local group, Hills for Climate Action, organises seminars like the one featuring Sebastian Pfautschwho has been heat mapping Western Sydney and advising how Penrith Council can reduce the urban heat island effect and help its residents make it through the summer.

The seminars are attended by council members, urban design professionals and interested members of the public. But she acknowledges that it is difficult to get GPs along, and she would like to make that happen.

“We’re really looking at ways of protecting the population because we know the built environment is not safe for everyone.

“If you have doctors who understand the problem, who get into influential groups, then you can infuse health into planning. But you can only advocate what you’re cognisant of. And if you cherish the community you live in, it is so important to actually advocate for them.”