The first generation of truly ‘freeborn Blaks are going gangbusters’, says rural generalist Dr Louis Peachey.

Dr Louis Peachey, a Girrimay and Djirribal man practicing as a rural generalist in Far North Queensland, tells the tale of life as Pinocchio, the many hurdles yet to come and, most poignantly, hope.

During my hour-long chat with the ineffable Dr Peachey, I was brought to near tears.

Amid an affecting recount of the journey to recognition as a “real person”, the crippling fallout from the Voice referendum and the struggles of rural generalism, Dr Peachey is filled with nothing but effervescent hope for the first generation of truly “freeborn Blaks”.

We started small…

How do we address health inequity?

The problems are systemic and far-reaching, says Dr Peachey.

“It might not be the positive story that you’re probably looking for, but if a man can’t be honest…

“We just haven’t gotten our head around what makes for a good society.

“We’re so frightened of the possibility that the poor might get something undeserved, that we make sure that they don’t get anything at all.

“But yet if we look at the wealthiest people in the country, we never asked the question: ‘does a mining magnate deserve to make that amount of money per day? Is there any human being on the planet who deserves to make that amount of money per day?’

“If our society is actually made suitable for the ‘other’, it’ll be suitable for everybody else in between.

“If I’ve got a private school system that is welcoming to gay kids, it is probably going to be welcoming everybody else.

“If I’ve got a health system that’s welcoming to the Aborigine, it’s probably going to be welcoming to everybody else.

“We just can’t get our head around that bit, we still have to make rules to penalise certain people.

“We keep missing the simple things [because] we want the brave new ideas.”

Speaking to the health minister at the time, Tony Abbott – who was looking for the silver bullet of inequity fixes – Dr Peachey spoke of the Mount Isa football team, whose bus broke down one Saturday.

“There were only a couple of rules to be on the football team: you had to turn up to practice sober and you couldn’t lift your hand to your missus.

“Because of this, the guys spent a lot of time sober and none of them lifted a hand to their missus.”

After breaking down in Never Never land, unable to find a new battery for the bus, the team fell apart.

In the search for “innovative” health fixes, Mr Abbott was missing the “simple answer”: it’s societal, aka “just fix the damn bus”.

“In my culture, if you ask a difficult question, you never expect an immediate answer,” says Dr Peachey.

“But white people love the silver bullet.

“The solutions that we have, I think, are an awful lot simpler than we believe because we’re not asking the right questions in the first place.”

So, where do the answers lie?

“Medicare needs a page one rewrite,” Dr Peachey says.

“About 20 years ago, at an Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association (AIDA) symposium, I sat down with John Deeble who created Medicare. He told me it was no longer fit for purpose – the man who wrote it decades ago.

“The premise of Medicare is acute medicine. It was never written for chronic conditions.

“It’s as if you had a factory to make Christmas cards and then suddenly, you want to build trucks. You can’t retool the workshop, you have to rebuild it.

“I’m just an old Aborigine who’s stepped out of the jungle and I can see this, why can’t the rest of you mob see this?

“Forgive my racism, but white people have a limited capacity to say, ‘is what we’ve built good?’

“The colonial project was white people bringing salvation to Blaks like me and helping us out with technology and all the other things that we got wrong.

“The white saviour complex is so convinced of its own wonderfulness that it’s impossible to interrogate.

“Look, I married a white people, my father was a white people, I love white people.

“It just drives me to distraction that this is plain as the nose of your face, and you can’t see it.

“I’m an old lefty, so it’s my football team who are in at the moment.

“Every day, Mr Albanese or Mr Butler talk about the bulk billing from urgent care clinics. But that’s not actually bulk billing because you’re making a collateral payment.

“You’re resetting the mindset that if the UCC can bulk bill and is running efficiently, then the GP down the road should be able to bulk bill too and if they don’t, they’re being mean and greedy.

“No, no, they’re not getting the $1.2 million extra on top that that the UCC is getting.

“What you’re selling to the world, it’s just a lie.”

What gives you hope?

“The thing that gives me great joy is looking at this incredible wave of young people coming on behind us,” says Dr Peachey.

“For those of us who want to grow old in the bush, I think we can feel really assured that there’s a cadre of incredibly good young doctors coming through who are going to provide an excellent service.

“If only we could get the rest of the world to understand that prices are going up and you’re going to have to fund better, fund more equitability, and we’re going to have to be cleverer.

“We’re spending money hand over fist on, say, transport that doesn’t need to happen and yet we can’t get the money spent on stuff that we really need.

“It drives you to distraction.”

What is day-to-day life like as a rural generalist in North Queensland?

“Mostly not too bad. But it is busy, and increasingly so,” he says.

“The substantive issue these days is the increasing population of older people, which isn’t being accounted for in our medical budget.

“At 60, that’s when healthcare really starts and that’s the group of people who are most in need.

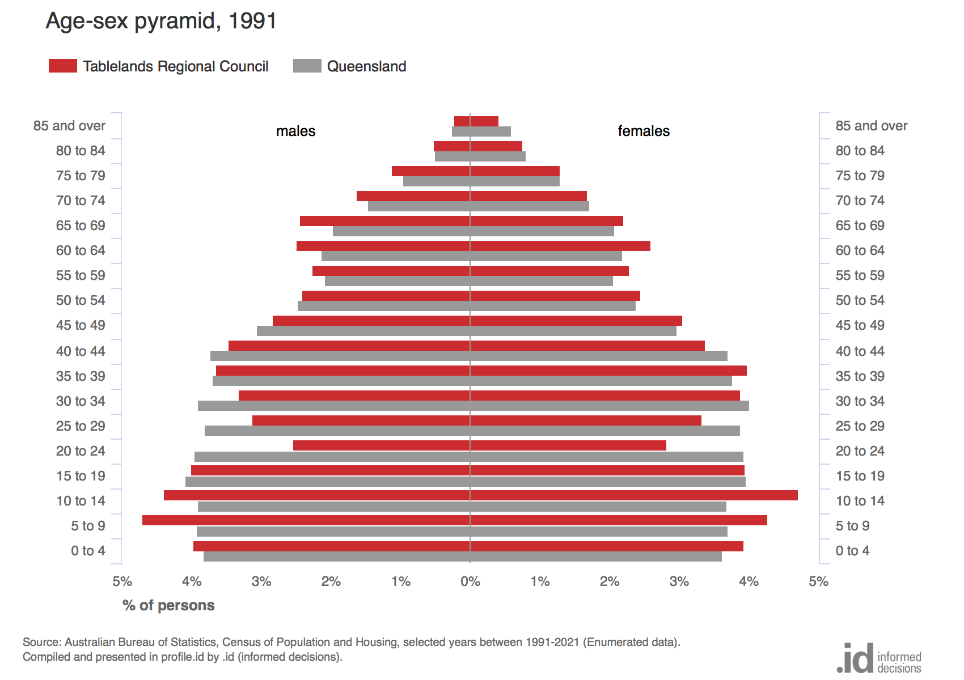

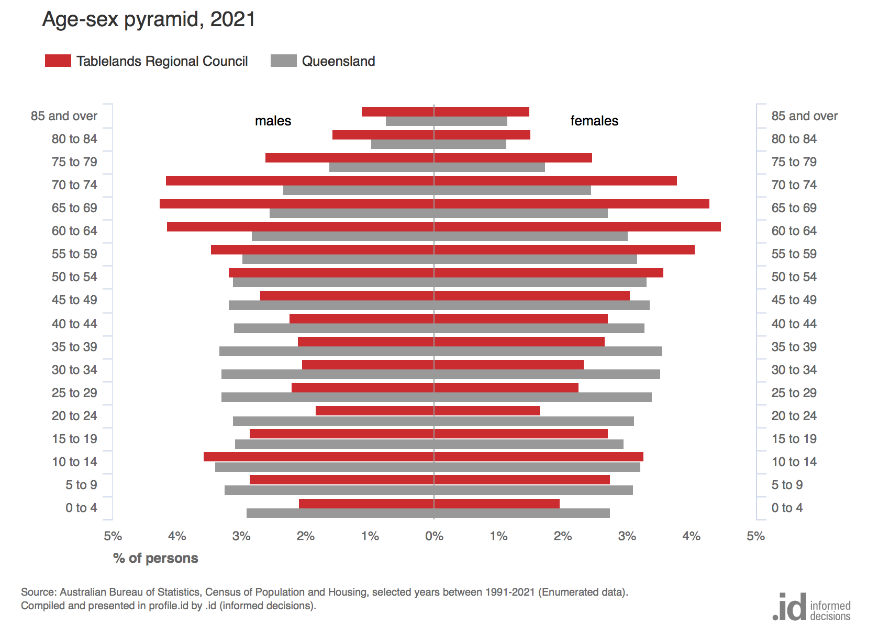

“If you compare the pyramid of 1991 to 2021 you will see the population has ballooned in the older age groups.

“It’s a perfect illustration of why a Medicare schedule from 1984, focused on acute care of a younger population, is no longer fit for purpose with the massive increase in older aged citizens who need good management of multiple overlapping chronic diseases.

“It’s fascinating to watch people who move here from the city, all irate that nobody bulk bills.

“When the Relative Value Study was published under Michael Wooldridge’s watch in 2001, the big peerage house in its audit found that what Medicare was paying was 50% of what was necessary to keep the lights on.

“And it hasn’t been indexed.

“The other thing that I found hilarious when the [Liberal Party] was in was Greg Hunt bragging about the bulk-billing rates being 80%-ish.

“If you think back to when you were a consultant for McKinsey, Greg, if you had told any of your businesses on McKinsey’s books, that they should be offering 55% discounts to 80% of their clientele … security would march you out the door.

“The cognitive dissonance of somebody who was a former business consultant for one of the biggest consulting firms in the world, then suggesting that this practice, which he’s lauding as being good, is at all sustainable…

“There’s not a snowflake’s chance [Greg] would have handed that advice to [his] clients [at McKinsey’s].

“As I get to be a much older Aborigine, looking at white people I just think, and I’m sorry for the racism again, but you mob is even less logical than I thought you was,” Dr Peachley says with a chuckle.

The other ongoing issue for rural generalists in the bush is a lack of guidelines around the number of patients per doctor and reasonable workload.

“Because of that, there’s nothing to stop governments from stacking it up until they block out the sun completely, which is just very unfortunate,” he says.

While this has been raised within ACRRM at a board level, it will likely take a vested interest to make change, as it so often does, says Dr Peachey.

How has the Voice referendum affected you, the community and health inequity?

While speaking at the Rural Medicine Australia conference last year, Dr Peachey ran a poll of all the people in the room who had read the Constitution.

“You’re not allowed into medical school unless you’re an uber nerd,” he says.

“And in a room of uber nerds, only 8% had read the Constitution.

“There were people that were ready to defend the sanctity of a document they have never read with their lives.

“I don’t understand how we can look at that and say that that’s logical.

“The problem with the rewrite was that everybody who was being asked about the rewrite hadn’t actually read the document.”

Dr Peachey was often asked in the aftermath of the no vote, “so, what now?’

“I was crippled for at least a month and a half after the vote,” he says.

“We told you what to do, and your mob said no. We had an idea on the table, you said no to our idea and that’s okay. Now it’s time for your idea.

“That was our last best idea, we didn’t have a backup plan.

“We don’t want to have constitutional power, we’re just asking for the right to speak and we want somebody to just maybe listen to us.

“The cognitive dissonance that was involved in that whole process was just mind numbing.

“I think where I’ve got to now, this far down the track after a lot of self-examination, while moving on I did stop and think, ‘but mum won’.

“My mother was born a non-person. She didn’t go to high school because her parents said, ‘you won’t be more than a domestic servant, getting an education is a waste of your time’.”

Her eldest son is now a homeowner of 40 years, has never been out of work in his adult life and is blessed with two wildly successful children.

Her youngest son, Dr Peachey, is an ineffable force of a rural generalist, with an eldest daughter who’s a well-established veterinary surgeon and whose youngest is in her final year of medical school and is, by all accounts, set to take over the world.

Dr Peachey speaks of his daughters with an awe that brought this writer to the edge of tears.

“Those two girls will be part of the first generation of freeborn Blaks. And they’re just going gangbusters.

“They’re just amazing. They’re anything any father could ever want.

“The sin that’s happened against Aboriginal children in this country was a theft of hope.

“But if that child grows up in a world where hope is possible, where they can have dreams, where they can have visions – looking at my daughters take the world by storm, looking at these young people coming through behind me at AIDA – it’s magnificent.

“As horrible as losing the referendum was, the flipside of it is, in the last generation two-thirds of my people came from poverty into middle class.

“And we did it with a minimum of help, not no help, but a minimum.

“What I learned from the referendum is that 40% of the country were with us. For every Blakfella, there were 12 whitefellas willing to stand beside us.

“So you know what? It’s not that bad.

“It would have been nice to have done it the easy way. For a while it did look like hope was on life support, but no, no, the hope is still there.

“And if you look back objectively at the last sixty years, it’s up and up and up.

“As bad as things might turn out to be – we’ve got a ways to go – but things have gotten better than they have ever been since colonisation started.

“Mum, it’s unfortunate that you didn’t get to high school and that was really unfair because at the time you weren’t even considered a real person.

“In fact, by the time your sons were born, they weren’t even real people.

“But like Pinocchio, they became real people.”

Dr Peachey said he hoped the younger generation would appreciate the paths paved by the elders.

“The elders have managed to pull two-thirds of [the Aboriginal population] out of poverty into the middle class,” he says.

“People like me were not even born a person, for Pete’s sake.

“And now I’m a doctor, I’m a senior medical officer in the town, I’ve got a fellowship with my postgraduate academic college – even for a white guy I’ve made it.

“That’s what the elders were busy doing, everybody.”

Wildcard question: what’s your favourite film?

A man of impeccable taste, one of Dr Peachey’s two favourite films is the cult classic Love Actually.

“It’s about the power of goodness, the power of decency and the power of kindness,” he says.

“As an Aborigine growing up in this world, I have been a recipient of that my whole life.

“Some good people that I need to thank: Dr Denis Lennox who established the Cunningham Centre Rural Training Facility at Toowoomba Hospital and ACRRM’s Vicki Sheedy.”

Dr Peachey also thanked his influential mentors – Dr Col Owen, Dr Jack Shepherd, Dr Tom Doolan and Dr Mark Craig – who were four of the six previous recipients of the ACRRM Life Fellowship, which Dr Peachey was also awarded.

“The other movie, which is my big, big, big favourite, is The Hunt for Red October. It’s magnificent.

“And not just for the implausibility of a Russian captain talking with a thick Scottish brogue in the guise of Sean Connery.”

At the end of the movie – spoiler alert – the captain, who’s defecting to the US, foils the Russian plot via a torpedo-on-torpedo clash.

“This is the combat tactics: by closing the gap before the weapon could arm itself, it stopped the greater damage,” says Dr Peachey.

“In my medico-political life as a doctor, one thing that I found every time is when the dogs come after you, turn directly into the bullet.

“Close the gap before they can get ready to arm themselves. Most of the time, it’s a winning tactic in politics.

“Run into the flames. It just works.”