Danish and Australian researchers are pioneering the use of visual technology for young cancer patients, helping to reduce parent and patient anxiety.

Researchers at the Danish Centre for Particle Therapy (DCPT) have become the first in the world to offer 3D simulation for proton therapy treatment, helping paediatric patients and their families to better understand and embrace treatment.

DCPT teamed up with UK software providers Vertual to provide a cinematic 3D simulation experience that replicates the treatment room in detail and shows the exact size and location of a patient’s tumour and how the beam will target it.

Over 30 young patients have watched the demonstration in the Aarhus University Hospital cinema, with DCPT informing Wild Health the experience has convinced some patients to undergo photon treatment when the proton alternative was not feasible.

“We have never had anyone not happy with the presentation,” said DCPT medical physicist Dr Klaus Seiersen. “I did have a 16-year-old patient who initially wasn’t too happy seeing the target size and location. However, he added that it actually looked exactly like he had imagined it, and he was happy to have it confirmed visually.”

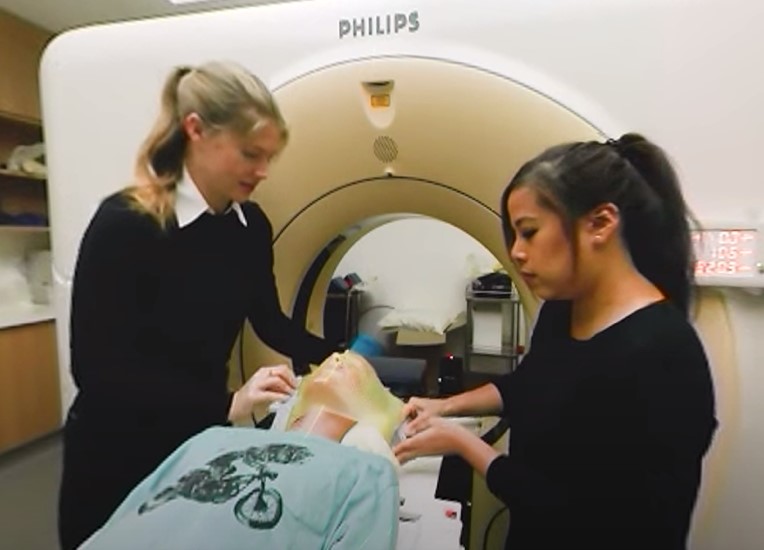

In Australia, Vertual’s 3D simulation software has been used by the likes of the University of Sydney to train radiation therapists, but there has been reluctance to offer it to patients because of the labor and time involved.

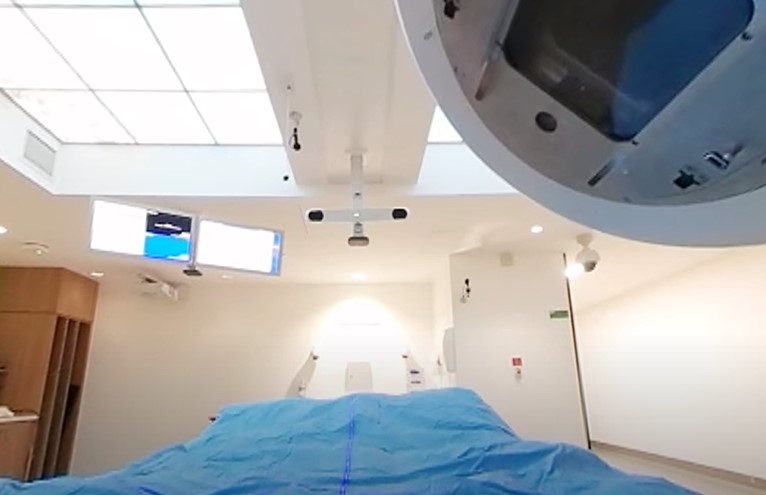

The Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre is challenging that kind of thinking with its offering of VR technology to paediatric patients. Patients don VR headsets to watch 360-degree recordings of a patient’s CT simulation and radiotherapy treatment, with the option to view the procedures as if they were the patient.

Peter Mac researchers recently published results investigating the benefit of VR for 30 patients aged six to 18 years old. Results suggest the use of VR lowered child and parent anxiety levels about the CT simulation.

After seeing the radiotherapy simulation, parent anxiety levels and their report of child anxiety remained low, while child anxiety increased, an expected outcome given treatment was imminent. However, only one in 30 patients opted for general anaesthesia, suggesting VR could help reduce the need for sedation. Sedation can mean a patient receives general anaesthesia 30 times in six weeks, carrying with it varied health risks for the patient and costing Peter Mac up to $30,000 per patient.

“We think it is best to offer VR prior to each procedure, so that when the ‘real’ procedure occurs, the patient is better informed as to what to expect, and therefore, likely to be less anxious,” Dr Nigel Anderson, Peter Mac’s principal research radiation therapist, told Wild Health. “This is not only our experience, but also the feedback we received from the children and their parents.”

Patients at Peter Mac can also opt to make their very own hero video during their radiotherapy journey where they dress up as a superhero, princess, music star or themselves to tell their treatment story. Head and neck patients can theme their masks along similar imaginary lines.

Years ago, a centre such as Peter Mac would have probably baulked at the prohibitive cost of using VR for patient care, but Dr Anderson pointed out that costs have come down considerably.

“It is essentially the cost of the headsets, which are now only a few hundred dollars each. The additional cost is for content development, which can be done in-house or outsourced. We now have our own team member capable of developing this content,” said Dr Anderson.

Which begs the question, why are adults not getting the same treatment option? Dr Seiersen believed most patients would benefit from the 3D simulation experience but that the main constraint was time, with each cinematic consult requiring a one-and-a-half-hour commitment.

Peter Mac confirmed they are undertaking research into offering VR to adult patients, a move that would be cheered by ex-oropharyngeal cancer patient Julie McCrossin. Mrs McCrossin had no doubt 3D or VR technology would have helped her mentally prepare for 33 consecutive days of treatment.

“If I had seen what was involved, I would have asked for help to cope with the experience in advance,” said the former ABC broadcaster. “I needed mild sedation, music, and sessions with a specialist cancer psychologist to cope with each 20-minute treatment.

“To send a patient into the radiation bunker without a clear comprehension of what is involved is to risk psychological stress and, in some cases, trauma.”

Dr Toni Lindsay, a clinical psychologist at Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, believed young cancer patients suited early 3D and VR initiatives but anything that helped to reduce patient stress or the need for sedation could benefit patients of all ages.

“Young people are more susceptible to vomiting, stress and heightened anxiety during treatment, but I know patients in their fifties and sixties that would benefit from the technology.”

Dr Lindsay stressed that it was important not to champion one technology but to give patients an array of options.

“The important thing is to give patients the potential to choose. Giving them autonomy at a time when a lot of things feel out of control is a huge benefit. The only danger would be if a patient had made a decision to not want to understand the treatment, but that’s why a huge part of care should be supporting patients to understand what they want and don’t want,” Dr Lindsay said.

Australia’s first centre to offer proton therapy, the Australian Bragg Centre, confirmed they are using 3D simulation software for training, and that they continue to monitor innovations in patient care in the buildup to commencing treatments in 2025.