New Australian research has explored the care GPs provide for cancer patients in the last year of their life.

GPs make an important and increasing contribution in providing care for cancer patients approaching the end of life.

General practice has a longstanding role in caring for cancer patients in their final months, particularly if patients choose to stop active treatment and to spend their remaining time at home rather than in hospital. But little was known about how end-of-life cancer patients interacted with GPs in an Australian context.

A new study, published in Family Practice, shows GPs play a key role in providing end-of-life care for cancer patients, with the majority of included patients having contact with their GP in the last three months of their life.

“These results reinforce the essential and central role of general practice for patients with cancer, and it is paramount that health policy continues to support and strengthen this role for the future,” the study authors conclude.

As part of the retrospective cohort study, researchers identified 10,267 Victorian adults from the MedicineInsight dataset who died of cancer. Of these, 7025 had at least one primary care encounter at a participating practice in the 12 months prior to their death.

Of the patients who had an encounter that was captured in the data set, 89% accessed GP care within the last three months of their life and 74% accessed care in the last month of their life.

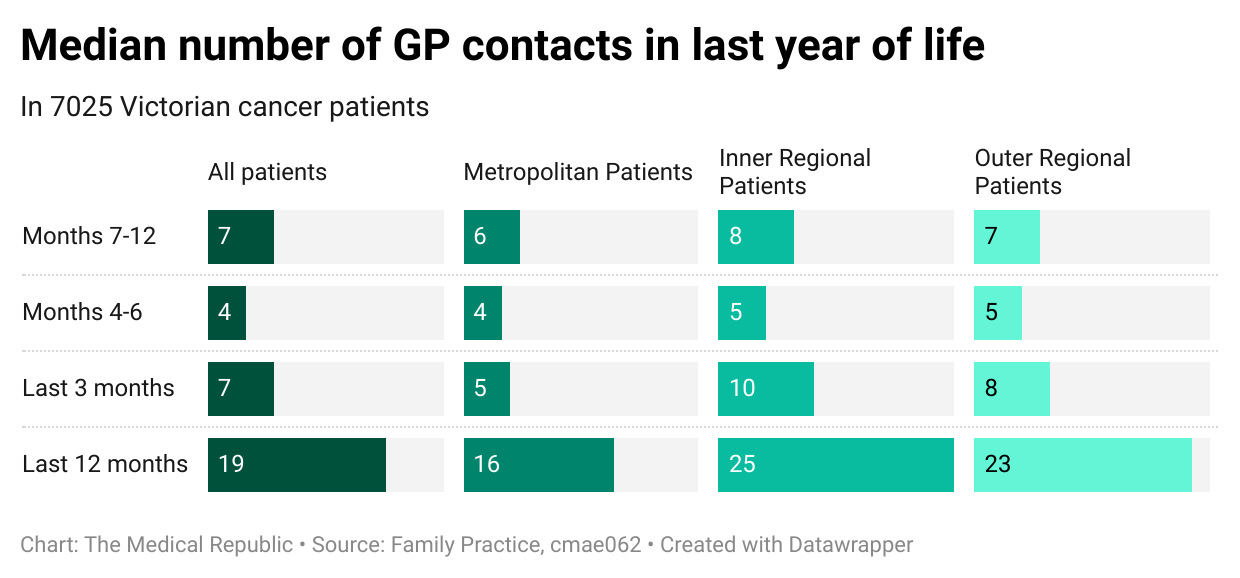

During the last 12 months of life patients had a median of 19 contacts with their GP, with a median of seven contacts during the last three months. Patients in regional areas had more GP contacts compared to patients who lived in metropolitan areas.

A greater proportion of patients in both inner and outer regional areas were prescribed opioids than patients in metropolitan areas (65% and 59% versus 53%), but a smaller proportion were prescribed other anticipatory medications for symptom management (17% and 16% versus 20%).

The authors felt the results reflect the need for regional and remote GPs to take on a larger role in providing such services, with specialist healthcare in these areas being less accessible and affordable compared to metropolitan settings.

“Access to specialist oncology and palliative care services may be limited in regional areas, and thus general practice services are likely accessed in order to meet these care needs, with GPs taking on a broader scope of practice with greater involvement,” the authors wrote.

Assistant Professor Matthew Grant, the study’s lead author, was not surprised by the findings, and was pleased to see GPs in regional areas were playing such an important role in the end-of-life process.

“It was probably reassuring knowing that GPs are stepping into this void to provide this vital care,” he told OR.

There was no difference in the number of times patients contacted their GP or the type of care processes provided between patients with different cancer diagnoses.

Related

The study was limited by only examining data from one jurisdiction in Australia (meaning the results may not translate to or be representative of other states and territories) and the limited nature of the available datasets (which did not contain details such as where the patient died, or whether palliative care services were involved in addition to GPs).

The authors acknowledged that selection bias was an issue, with the Medicinewise database including only “active” patients who had at least one GP contact event in the last 12 months – meaning patients who visited different GPs were not captured.

“For patients in the last 12 months of life with cancer diagnoses, it would very much be expected that they would have at least one contact with a GP in the last year of life, given the complexity of managing these patients,” Professor Grant told OR.

“We understand this this is an imperfect manner to select our population, and may lead to minor selection bias, but there were no other viable alternatives. We firmly believe this approach (which was debated within our expert group of academic GPs and palliative medicine physicians) was the most fitting approach to dealing with this challenge.”

Professor Grant, who works as a GP and palliative care physician in the Netherlands, felt there was significant value in having GPs taking an active role in end-of-life management.

“The GP knows the patient and the family and has likely been involved with the patient for an extended period throughout diagnosis and treatment. They will have likely already discussed numerous times what the patient wants and know the care network around the patient. They are able to provide this care in the home environment, enabling patients to die at home if they wish.

“From a health service perspective, GP care makes sense. Most patients at the end-of-life do not have complex care needs and can access the most appropriate care through their GP. When patients have more complex needs, specialist palliative care services can be involved.

“It is also likely that they are also the GP for the partner or other members of the family, and are there to provide bereavement care after death if needed.”