Whether you believe the whistle blowers and politicians or not, the ABC’s Four Corners program this week probably marks a point of no return for business as usual for most of our major consulting firms.

Monday’s Four Corners program delivered meaningful blows to the credibility and integrity of the business tactics of our four large accounting-based consulting firms, including some specifically targeted examples from the health sector.

It was enough to almost certainly ensure that significant, probably regulatory based changes, will be need to made by both state and federal governments to the operational relationship with these firms moving forward.

The most compelling immediate question however is, what do government departments do with current contracts and relationships and near term contract negotiations, given that, if we are to believe and extrapolate some of the material aired last night by the whistle blowers and politicians, a significant proportion of contracts with these four and other major consulting firms are certainly compromised from a public perspective and potentially now from an ethical perspective at least?

Four Corners opened last night’s program by putting the health sector firmly in the cross hairs of public concern by pointing out that despite a new Labor government pledging to curb the influence of consultants, it has already appointed three department heads straight from the big firms.

The first of these appointments the program detailed was our new Federal Health Secretary Blair Comley, who the show pointed out had spent the previous five years with Ernst & Young (EY), although his time was with a boutique firm owned by EY called EY Port Jackson.

Comley comes in for no further specific inquiry by the program but putting him up front as an example of consultants moving between significant government and private sector consulting roles in a program that goes onto to trash the credibility of such arrangements must have some in the Department of Health and Aged Care (DoHAC) worried already on matters of transparency moving forward.

The other two department heads named by Four Corners included Jim Betts, who was briefly an EY partner, and is now secretary of the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts; and Natalie James, now in charge of the Department of Employment after four years with Deloitte, a firm that comes in for particular criticism for probity issues surrounding its Services Australia contract to overhaul its IT systems, following a meltdown of the system early in the covid pandemic.

Both Labor and Green senators who are sitting on current senate inquiries into the consulting firms were interviewed expansively by the program and outlined specific examples of how the consulting firms are operating in a non-transparent and potentially conflicting manner with the federal government.

Labor Senator Deborah O’Neill told the program that there have been significant failures from all the big four accounting-based firms that warrant investigation and potential regulation moving forward.

“We know they share staff. We know that information moves around between them. We know that information moves not only between players in the sector but between government and into the sector. And I don’t think that PWC is the only company to have figured out that it might be financially advantaged [by this],” she said.

Significant allegations with regard to improper behaviour by KPMG were made by a whistle blower: that KPMG regularly overcharged for services, charged for services that didn’t occur and that, at one, point nearly all invoices issued by the firm had “errors in them”.

KPMG denied all the allegations of the two whistle blowers featured on the program.

But Senator O’Neill was not buying what KPMG was saying.

“These companies operate a land and expand model where they sometimes under-price the first piece of work and once they get in then they expand their reach through familiarity,” she said.

“The whole business model of these companies is billable hours.

“The longer they stay there, the less efficiently they do the job.

“It’s about getting very close to government, finding out what is going on, using the contacts and then growing the business.”

The program went on to detail an example of an ex-Defence Department employee, who although banned for 12 months under existing regulation from working with a group that is engaged by the department, continued to talk to Defence staff and feed information back to key staff in KPMG.

KPMG staff acknowledged in a leaked email that this had been invaluable to them securing more work.

Over the past five years, almost 100 former Defence staff have moved to KPMG, according to the program.

Greens Senator Barbara Pocock, who has been a key figure in the PWC tax scandal inquiry, told the program that “every dollar you spend on a consultant, you remove the possibility that a senator can ask a question in [Senate] estimates [because] they aren’t exposed to estimates or questions on notice unless they are inside an inquiry”.

“So a whole lot of the key transparency devices and tools for our parliament are prevented from looking at the big spend on consultants … a big impact on our democracy,” she said.

Pocock went on to question not just the commercial motives of the big firms, but the motive of certain governments in using consultants in this manner.

“Is moving so much of the government’s spend outside the public view to give certain governments cover for what they want to do?” she asked.

“Defence [for example] is a black box…we need a lot more transparency, a lot more accountability and evaluation of the contracting services into Defence and more broadly,” she said.

The program pointed out that KPMG has at least 12 different business names, which made it very hard to understand from looking at government websites how many contracts they’ve been awarded, what the value of those contracts actually was and what they were called when the contract was awarded.

Adam Evans from Anywise Consulting went to the trouble of finding all the contracts and aggregating them to give everyone a better picture of what might be going on.

In terms of KPMG, he found that in the last 10 years it had been awarded 3673 government contracts to the value of $1.63 billion and that with those contracts 1908 contract amendments eventuated, amounting to $945.8 million.

That amounted to a 60% uplift of original contract value being obtained by KPMG and went directly to a point being made by senators Pocock and O’Neill that these firms appeared to be operating “land and expand” strategies.

“Management advisory 101…get a contract, make it longer and sell more people in,” Evans told the program.

The program outlined several examples of the moral hazard faced by senior public servants in their roles.

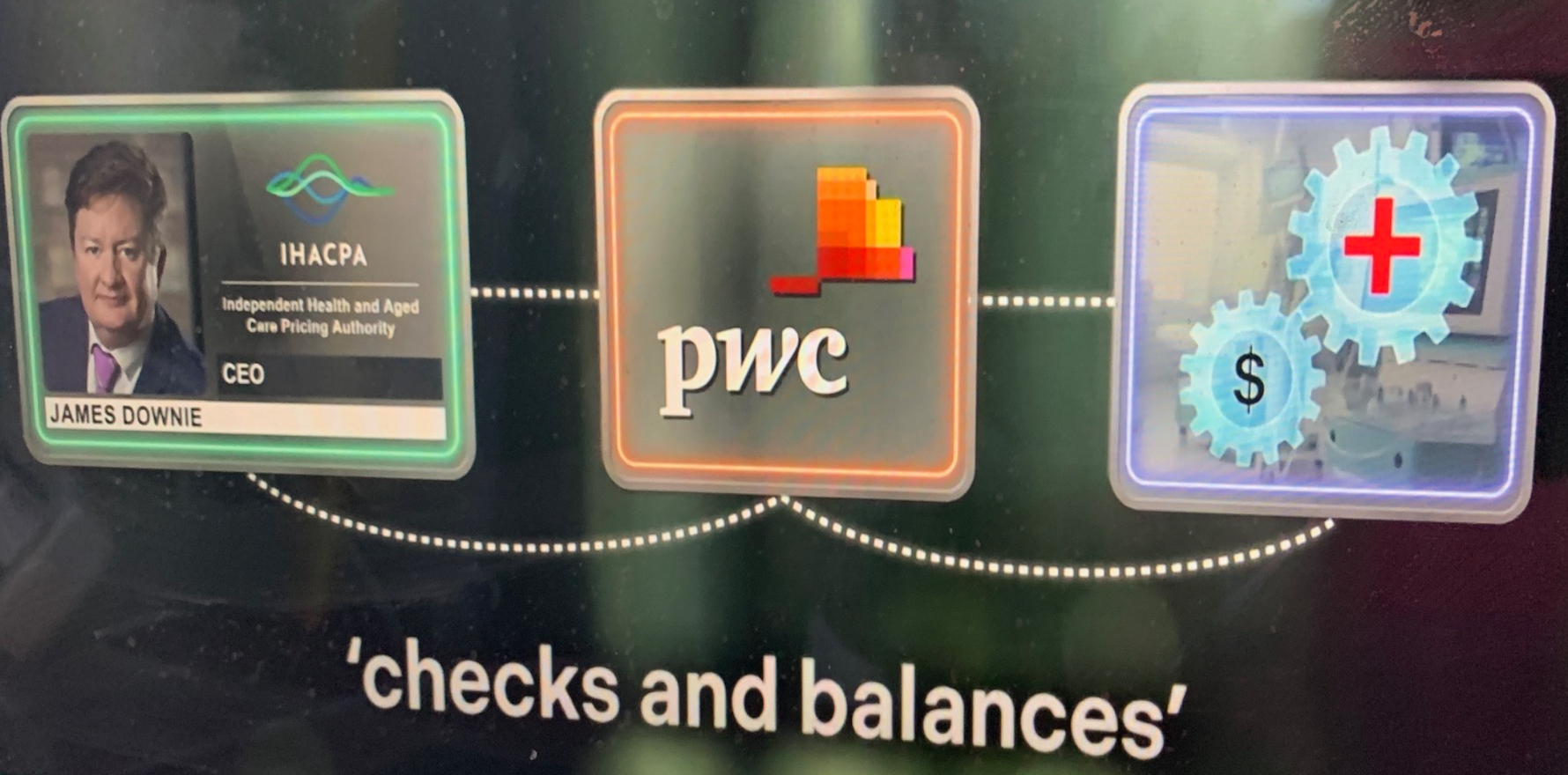

The second example the program outlined from the health sector was that of the appointment of James Downie, the past CEO of the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority, a government agency charged with advising on the price of hospital services and medical equipment, to PWC in September last year.

According to the program, Downie had said that in this case there was no requirement from the agency for any cooling off period before he worked for a past contractor, as had been the case with the KPMG Defence Department example above.

There is no suggestion that Downie did anything illegal by joining PWC and then consulting back to his old employer. Four Corners suggested however that there was a clear case of conflict of interest.

Another key example of non-transparency in dealings raised by the program was a Deloitte contract to overhaul the myGov website after the site was overwhelmed early in the covid pandemic.

Senator O’Neill told the program that “there are lots of probity questions to be answered here”.

According to the program Deloitte was awarded a $9 million contract in March 2020 with the Digital Transformation Agency, without any competitive tender in place and that this contract eventually ballooned to being worth $47 million.

The contract was the subject of a scathing report from the Auditor General, which said the contract had failed in 12 key areas of evaluation including “offering taxpayers value for money”.

The Four Corners program did not land definitive examples of provable corruption on the part of the four big firms.

But that probably does not matter now.

It outlined enough examples of impropriety on the part of various firms, and clear examples of operational business models that seek to exploit weaknesses in governance and regulation on the part of governments – all from recent federal inquiries – to create a public stake in the ground. There is very little governments can now do but respond and seek to rapidly ameliorate a situation in which public confidence in the relationship between these firms and government is irreparably damaged.

There is no way back.

Governments working with all these firms are going to have to work out short-term operational procedures to protect themselves (and the public) from the damage that could be caused by existing and near term contracts and relationships operating under this cloud. They will have to rapidly develop effective governance and regulation to ensure that what seems to have been exposed clearly in recent government inquiries, and even more publicly by this program, ceases to be a part of the operational relationships between these firms and governments moving forward.