For the one in three menopausal women who will have depression, there’s more on offer than the standard treatments.

Depression is a significant issue in menopause but there are treatments, including for those with estrogen-dependent cancers, a leading Australian psychiatrist says.

Depressive symptoms can be far more severe than either before or after menopause, Melbourne psychiatrist Professor Jayashri Kulkarni told the 25th Australasian Menopause Society Congress last month.

Professor Kulkarni, director of women’s mental health institute HER Centre Australia, said that among all demographic groups, women aged 45 to 55 have the second highest suicide rate in Australia, after men over age 84 years.

“Middle-aged women are dealing with rearing adolescent children, being quite senior in the workplace, work stresses, perhaps contending with relationships that are a bit tired and all sorts of aspects of ageing that can impact on her own perception of herself,” Professor Kulkarni told Oncology Republic.

But she said the mental health “tipping factor” was menopause and the sudden changes in hormones. Considering what is known about the effects of estrogen on the brain, it was not surprising that women could suddenly experience depression, she said.

“Estrogen, progesterone and testosterone – but particularly estrogen – are very potent neurohormones. We think of them as just gonadal hormones that are responsible for reproduction, but they have big effects in the brain in terms of modulating brain chemistry. There are also protective effects of estrogen in brain circuitry.

“It’s not a case of ‘let’s just wait and see’, because that’s not going to fix it for someone whose life is being terribly disturbed by the menopausal process.”

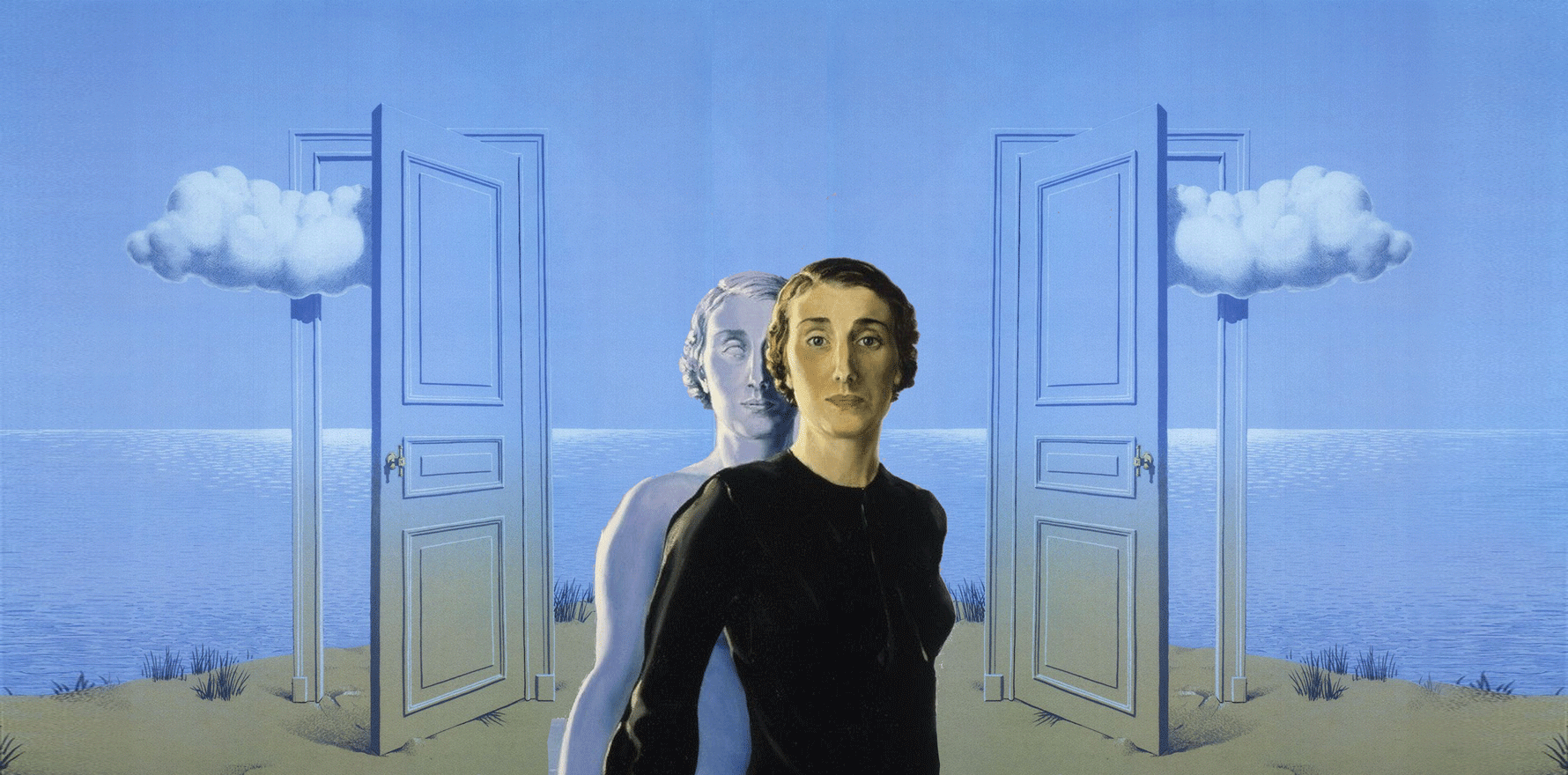

Professor Jayashri Kulkarni

“When estrogen levels fluctuate and decrease, a whole lot of things can go wrong for vulnerable women.”

For women who have had estrogen-dependent breast cancer, Professor Kulkarni said a low-risk option is the non-drug treatment transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS).

“TMS is a very acceptable form of treatment for depression in a number of conditions and it has an extensive number of trials and validity. This is another form of treatment that may be very useful for women who don’t want an antidepressant, for example.

“Brain stimulation techniques are getting better and better as we speak. And there are a number of clinics that are available for TMS for depression, with good results.”

Professor Kulkarni said selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) were another option and delivered the positive estrogen effects of HRT to the brain but without hitting the body.

“SERMs work on the brain estrogen receptors and the bone estrogen receptors, but they don’t have an estrogen effect in the breast, uterus or ovaries.

“There’s a few of them on the market brought out for treatment of osteoporosis, but it may be that if somebody is depressed because they suddenly went into a rapid menopause because of ovariectomy or some other process, that this might be something in the future that is of use for her.

“However, we haven’t got to the stage of trialling it in depression in women with cancer, so we can’t comment on data from a trial like that.”

Professor Kulkarni said SSRIs could be useful for some women and were another alternative for women with estrogen-dependent cancer.

Not every woman will have severe depression during menopause, she said.

“But there is a population who really struggle with either first-time depression that hits at about 45, or the woman who has had depression and it’s been nicely treated in the past, and all of a sudden it just goes out of her control again around the mid-40s.”

Women in mid-life have a “particular form of depression”, Professor Kulkarni said.

“It’s not just a tearful, sad, low mood, but there can be a lot of anger, rage and hostility. They’re not easy for people to either understand or be the recipient of, as partners, family or work colleagues.

“I see women all the time who have lost their quality of life in many ways, with problems at work, problems in their relationships, difficulties with parenting and just not enjoying life.”

Standard antidepressants were not always effective for this type of depression, she said. “It might mean that there has to be a hormone strategy that’s involved, or at least an understanding of what is going on for her that this problem has occurred.”

“But there is a significant number of women who haven’t got a response or enough of a response. And there hasn’t been enough research because it’s not been seen as an important area to fund.”

There was a common belief that menopause was just about hot flushes, but it could also be a significant issue for the brain and mind, Professor Kulkarni said.

“There can be fresh depression in someone who doesn’t have a troubled life.”

According to Australian Menopause Society figures, around 20% of menopausal women have significant mental ill health and about 60% have physical and mental menopause symptoms.

“This is not a minor issue,” Professor Kulkarni said. “It’s not a case of ‘let’s just wait and see’, because that’s not going to fix it for someone whose life is being terribly disturbed by the menopausal process.”