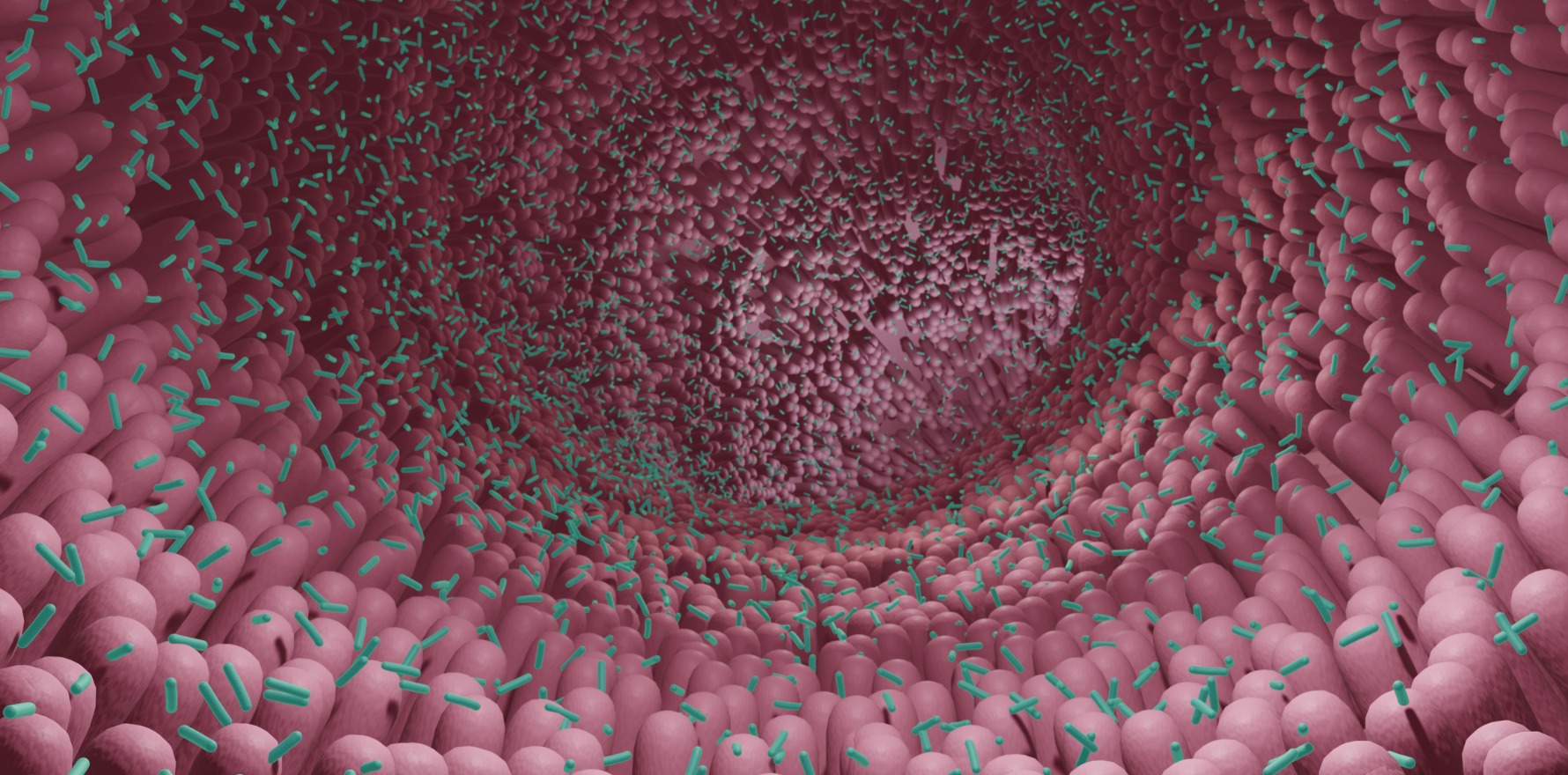

Research around the microbiome and its potential role in cancer treatment has come a long way over the past decade.

Research and practice around the microbiome, and its potential role in cancer diagnosis and treatment, have come a long way in the past 10 years, and innovations are starting to pay dividends.

Dr Jennifer McQuade, assistant professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Centre, presenting at the recent American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) meeting, said patients were looking for ways to boost their chances of success with immunotherapy.

“When I tell my patients with melanoma starting immunotherapy that they essentially have a 50% chance of their tumour responding to immunotherapy, one of the most common questions that I get is, ‘Doc, is there something else that I could be doing?’,” she said.

“And so that’s really what we’ve set about to address in a biologically rigorous way: is there something that patients could do that might actually influence their outcomes?”

Microbiome specimens collected from people starting immunotherapy showed little concordance in what constituted favourable taxa, and this could come down to sampling methods or differences in sequencing, said Dr McQuade.

Indeed, this heterogeneity and the lack of reproducibility were among the greatest challenges facing researchers in this area, which made developing a probiotic or faecal matter transplant (FMT) problematic. Nevertheless, some small human studies with FMT and probiotics have shown promise.

Dr McQuade’s team had embarked on a series of clinical trials to address the question: “Can we modulate the microbiome via a whole foods dietary approach and change immunity?”

The research kicked off with a dietary survey of patients taking systemic therapies for melanoma and it found that patients that had a sufficient dietary fibre intake had improved their progression-free survival.

A feasibility and safety study of a high-fibre controlled feeding study in patients found compliance was reassuringly high. The biggest changes in microbiome occurred in those who started with the lowest fibre intake, suggesting they were the best target for intervention.

The phase 2 trial is currently recruiting patients with melanoma who are actively receiving immunotherapy and who habitually consume less than 20g of fibre a day.

Until they were at the point where there’s enough known to produce a magic pill, it would down to having a good diet, and while acknowledging that taking a pill was easier than changing a diet, Dr McQuade said the whole-diet approach was important.

“Maybe the whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” she said.

While the gut microbiome is probably the best studied of the many microbiome communities hosted by the human body, researchers have started looking at the lung microbiome and how it could affect tumour progression and response to immunotherapy.

The lungs have long been thought to be sterile, and it’s only in the past 10 years that they have been found to host a dynamic microbial community with a role in immunity and inflammation.

Professor Maija Kohonen-Corish, head of the Lung Cancer Centre at Woolcock Institute in Sydney, leads a research group investigating the microbiome – lung, oral and gut – in lung cancer.

“Our approach is to study the gut, lung and oral microbiome from the same patients taken at the same time,” she said.

“This way we can compare the unknown factors (lung and oral microbiome) with the better-known gut microbiome and draw conclusions from that.”

She said research on the oral microbiome and lung cancer was quite promising, pointing to research that found decreased oral microbiota alpha diversity, but not beta diversity, was associated with an increased risk of lung cancer in people who’d never smoked.

As yet, no studies have investigated the effect of the local airway microbiome on immunotherapy response, though research in animals and small patient cohorts suggested there may be potential to modify the microbiome as a potential therapeutic strategy. However, Professor Kohonen-Corish said it was too early to say what the most likely therapeutic targets or interventions might be.

In recognising that cancer therapy side effects could be a major barrier to effective treatment, Dr Hannah Wardill of the University of Adelaide was investigating the microbiome and outcomes in cancer therapies.

“The research looks at how various cancer treatments – chemotherapy, radiotherapy or some of these newer agents like tyrosine kinase inhibitors – affect the composition of the microbiome, and how those changes then affect an individual’s response to treatment and complications that they develop,” she said.

The team recently completed a feasibility study on using autologous FMTs in patients with blood cancer to reduce the impact of chemotherapy on the microbiome. The patient’s stool sample was collected before treatment, and then processed and transplanted after treatment to restore the patient’s original microbiome.

“People with blood cancer undergo very high doses of chemotherapy as well as antibiotics, and their microbiome is severely damaged – and with that comes a range of different complications, including infections,” Dr Wardill said.

Supporting the microbiome in this way would potentially mitigate some of the treatment complications and would enable patients to tolerate treatment better and therefore receive the required treatment dose, she said.

“The strength of the microbiome and the huge impact that it has on its host is because of the diversity of species within it; it acts as a whole, not as individual species,” Dr Wardill said.

“However, in saying that, it may be that we identify that faecal transplant is effective, but it’s effective when strains A, B and C, work together.”

The goal, she said, was to move into more standardised therapies that could be produced on a large scale, rather than relying on individual faecal donors.